DNA ancestry tests have become incredibly popular, with millions of people using them to uncover details about their origins, heritage, or ethnic identity. These tests work by analyzing a person’s DNA and comparing it to reference populations. The results provide probabilistic estimates of similarity to these groups, not definitive proof of belonging to them. For example, a test might suggest someone’s DNA is similar to that of a particular regional or ethnic group, but this doesn’t confirm their cultural or social membership in that group. These markers are indicia—clues—rather than criteria, or definitive rules, for group membership, a distinction that is often misunderstood.

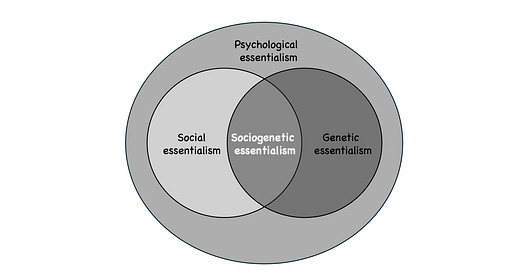

This misunderstanding stems from psychological essentialism, a way of thinking where people believe that categories like race or ethnicity are defined by inherent, unchanging “essences” that make members of a group fundamentally similar and distinct from others. In short, there are four core beliefs of psychological essentialism: (1) categories represent fundamentally different types of people; (2) category boundaries are rigid and absolute; (3) members within a category are highly similar; and (4) these characteristics come from internal essences. When people apply this mindset to social groups, they assume that groups like races or ethnicities have fixed, biological foundations, even though science shows these categories are socially constructed and not strictly defined by genetics. And when DNA becomes the placeholder for these essences, we may get things utterly wrong.

The term “sociogenetic essentialism,” describes what happens when people perceive DNA as the essence defining social categories. This occurs when individuals interpret DNA ancestry test results as confirming the biological reality of social groups. For instance, if a test indicates a percentage of “West African” ancestry, someone might believe they are inherently part of a distinct racial or ethnic group, overlooking that these percentages are statistical approximations based on limited reference data. This misinterpretation arises because people confuse indicia (the markers used in tests) with criteria (definitive proof of group membership), a confusion fueled by the intuitive nature of essentialist thinking.

The societal implications of sociogenetic essentialism are profound, and I find them concerning. By reinforcing the notion that social groups are biologically distinct, this mindset can perpetuate harmful stereotypes, discrimination, and exclusion. For example, believing DNA defines ethnicity might lead to assumptions about a person’s culture, behavior, or worth based solely on test results, ignoring the complex social, historical, and environmental factors that shape identity. Such beliefs are very intuitive and often emerge early in life, making them deeply ingrained and difficult to challenge. This is further complicated by the public’s tendency to view scientific tools like DNA tests as authoritative, even when their limitations aren’t fully understood.

To tackle these issues, there is a need for clear communication about what DNA ancestry tests can and cannot do. Without proper explanation, the use of ancestry informative markers can unintentionally reinforce sociogenetic essentialist biases. For example, test reports that present results as percentages of ancestry, like “30% Scandinavian,” without clarifying their probabilistic nature may lead users to assume these categories are fixed and biologically meaningful. I believe strongly that education is key here—people need to understand that social categories are constructed and that human genetic variation doesn’t neatly align with traditional notions of race or ethnicity. This can help prevent the misuse of test results in ways that deepen division or prejudice.

While I see these tests as valuable tools for exploring genetic heritage, I’m concerned that their results are easily misinterpreted through the lens of psychological essentialism, particularly sociogenetic essentialism. This can lead to misguided beliefs about the biological basis of social groups, with serious consequences for social cohesion and equality. Greater clarity is required in how test results are presented and interpreted, and I urge both scientists and the public to recognize the probabilistic and limited nature of ancestry inferences. By fostering a better understanding of these tests, I hope we can appreciate their benefits while avoiding the pitfalls of essentialist thinking that could deepen social divides.

(The full article that I wrote with Michal Fux will soon appear in History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences; for the broader discussion see my book Ancestry Reimagined).